A blinding light like thousands of strobe lights—that’s how Toshiko Tanaka described the morning, 80 years ago today, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

On Aug. 6, 1945, the Enola Gay B-29 Superfortress bomber delivered its payload, dubbed Little Boy, onto the unsuspecting civilians of Hiroshima. Three days later, a second bomb— Fat Boy — fell on Nagasaki. The bombing led to the Japanese official surrender in World War II on Sept. 2, 1945.

By the end of 1945, about 210,000 people, mostly Japanese civilians and forced Korean laborers, had died. Some perished instantly in the blasts, others died later on from radiation poisoning. Pregnant women lost children in the aftermath, and thousands more civilians would fall victim to cancers and other side effects over the following decades.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain the only two cities ever to be targeted by nuclear weapons. Tanaka, who was just 6 years old when the bomb fell, told CBS News in 2020 that both remain scarred by the horrors unleashed by President Harry S. Truman and the scientists of the Manhattan Project in the early hours of that quiet August morning.

Bombing of Hiroshima

U.S. Army/Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

U.S. Army/Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

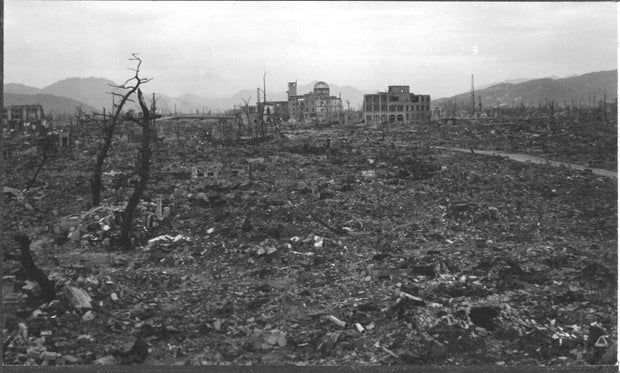

In the wake of Little Boy’s devastation, a stone building, five stories tall with blown-out windows and a crumbling roof, remained standing, despite its proximity to the bomb’s hypocenter and the vaporization of everyone inside.

Then known as the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, the building was gutted by the blast, but its ashen steel dome, which shouldered the brunt of the overhead explosion, endured as a symbol of the city’s resilience. Today, the structure is a part of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial.

Museum of World War II

The atomic detonation, and ensuing firestorm, destroyed or heavily damaged 60,000 buildings in Hiroshima—two-thirds of the city’s total structures. This image, taken by U.S. military reconnaissance, shows the city before and after the Enola Gay flew overhead.

AFP/AFP/Getty Images

Three years after the bomb fell, Hiroshima still resembled a wasteland of crooked steel and charred rubble. This photo, dated 1948, shows how life was beginning to sprout from the desolation, with a handful of buildings dotting the ruined landscape.

Carl Court / Getty Images

Getty Images

Today, Hiroshima is a booming metropolis of 1.2 million people—nearly 3.5 times larger than the city’s estimated 1945 population of 350,000. After the bombing, the population had cratered to around 83,000.

Bombing of Nagasaki

U.S. National Archives

Nagasaki saw less overall destruction than Hiroshima, primarily due to the city’s geography and urban design. Still, 14,000 structures—27% of all buildings in the city—were destroyed when Fat Boy detonated above Nagasaki. Only 12% of the regional capital’s structures remained undamaged when the dust settled on the Southern Japanese island.

U.S. National Archives

U.S. National Archives

By 1948, Nagasaki had been slow to recover. Temporary structures had started to emerge a year after the bombing, but citywide rebuilding wouldn’t begin until the passage of the Nagasaki International Culture City Reconstruction Law in 1949. Three years after nuclear weapons were deployed, charred tree trunks, stripped of their branches, stood near a sacred Torii Gate that survived the blast.

Kiyoshi Ota / Getty Images

Getty Images

Today, Nagasaki is home to nearly 400,000 people, up from the estimated 263,000 that called the city home 80 years ago.

Nuclear warfare, 80 years later

Today there are nine nuclear-armed nations—the United States, Russia, China, the United Kingdom, France, North Korea, India, Pakistan and Israel—and fear of nuclear war is once again on the rise, thanks to heightened regional tensions in the Middle East and the continuing war in Ukraine.

On Wednesday, at a ceremony marking 80 years since the bombing, Hiroshima mayor Kazumi Matsui said that those conflicts “threaten to topple the peacebuilding frameworks so many have worked so hard to build”

“Policymakers in some countries even accept the idea that nuclear weapons are essential for national defense. This disregards the lessons the world should have learned from past tragedies,” he said, with the now-rusting steel dome of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial marking the skyline behind him.